Man is an ‘embodied spirit’ and for this reason the Word of God invites all believers to love every man and the whole man in his mysterious unity of body and spirit. Thus, after reflecting on corporal needs, we can now more easily explore the complex reality of the spiritual needs of man, who was created in the image and likeness of God. Indeed, what makes man great, noble and immortal is his soul, the ‘life-giving breath of the Spirit’ (Gen 2:7); his heart that yearns for peace, for joy, for courage, for consolation, for truth, and for life without end. These are all aspirations that will find fullness and completion only in God in heaven. For this reason, the great Augustine, after experiencing the ephemeral joys of the world, found peace and joy only in the merciful arms of the Father: ‘Lord you made our hearts for you, and they are troubled until they rest in you’.

Man is an ‘embodied spirit’ and for this reason the Word of God invites all believers to love every man and the whole man in his mysterious unity of body and spirit. Thus, after reflecting on corporal needs, we can now more easily explore the complex reality of the spiritual needs of man, who was created in the image and likeness of God. Indeed, what makes man great, noble and immortal is his soul, the ‘life-giving breath of the Spirit’ (Gen 2:7); his heart that yearns for peace, for joy, for courage, for consolation, for truth, and for life without end. These are all aspirations that will find fullness and completion only in God in heaven. For this reason, the great Augustine, after experiencing the ephemeral joys of the world, found peace and joy only in the merciful arms of the Father: ‘Lord you made our hearts for you, and they are troubled until they rest in you’.

It should be observed, before exploring the individual works of charity, that in addition to ‘mercy’ the word ‘spirit’ dominates, almost as if to emphasise, as regards corporal works, that the principal actor of such works is not ourselves but the Spirit that God infused in our hearts, that promised by Jesus Christ before he went back to the Father and who will make us know the whole truth. Thus it is of fundamental importance to remember that whereas in corporal works it is prevalently our hands that work, illumined by faith, to give bread, clothes and lodging, to quench thirst, to heal, and to visit the person of Jesus incarnated in every man in need, in spiritual works it is, instead, the Holy Spirit who is the principal actor, the source and the soul of every deed of mercy. It is the Holy Spirit whom we must with fervour and insistence invoke; only if we are full of God and love Him will we manage to effectively perform these works that touch on the deep mystery of God and the essential needs of man. ‘He is an intelligible light and help in the search for truth; meek and light is his advent; fragrant and soft is his presence, very light is his yoke. Indeed he comes to save, to heal, to teach, to exhort, to strengthen and to comfort’. Jesus promised us: ‘I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counsellor, to be with you for ever, even the Spirit of truth’ (Jn 14:16). ‘Souls that have the Spirit in them are illumined by his presence; they also become holy and reflect grace onto other people’ (St. Basil the Great, PG 32,107). He is the light of our minds, the splendour of our souls (St. Hilary, PL 10,50). But he is a gift and a presence that we must ask for every day: ‘I called upon God and the spirit of wisdom came to me. I preferred her to sceptres and thrones’ (Ws 7:7). ‘If any of you lack wisdom, you should pray to God, who will give it to you’ (Jas 1:5). We must love wisdom like a sweet bride in the intimacy of a home; it is specifically the Book of Wisdom that gives us the following evocative advice: ‘I loved her and sought her from my youth, and I desired to take her for my bride, and I became enamoured of her beauty…she understands turns of speech and the solutions of riddles…Therefore I determined to take her to live with me’ (Wis 8:1-21).

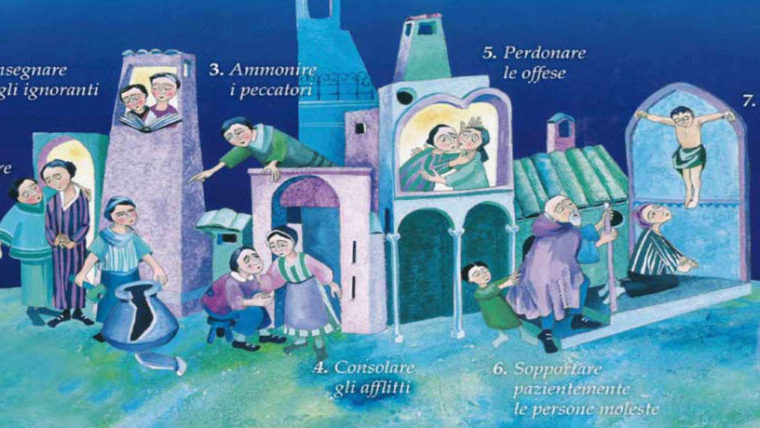

Those who have read my previous observations will be able to observe that ‘Works of Corporal Mercy’ almost all refer to chapter twenty-five of the Evangelist Matthew whereas works of spiritual mercy are to be found here and there in Holy Scripture, which on this subject refers to the Prophets, to the Books of Wisdom, and to the historical books. As they are proclaimed today by the Catechism, all fourteen of these works were cited for the first time by the ecclesiastical writer Lactantius (250-325). The repeated number seven is a sign of completeness. What forms the foundation of these works is ‘Mercy’. It indicates the culminating point of love because it testifies to permanent faithfulness that knows how to achieve forgiveness and self-giving. The misery and the hearts of man are involved. A person, that is to say, opens himself to the needs of the other and does not fail to provide him with his active participation and sharing.

In the appeal to mercy as it is found in the Bible, more emphasis is laid on the tenderness and goodness of God. It is starting with this dimension that one discovers the maternal features of the love of God. God is like a Father for Israel but He loves with the tenderness and the care of a Mother. When we read some passages, we can only be moved, and to the point of having tears of exultation and joy: ‘But Zion said, “The Lord has forsaken me, my Lord has forgotten me.” “Can a woman forget her suckling child, that she should have no compassion on the son of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you”’ (Is 49:14-15). ‘When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son, the more I called them, the more they went from me. ..Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk, I took them up in my arms; but they did not know that I healed them. I led them with cords of compassion, with the bands of love, and I became to them as one who eases the yoke on their jaws, and I bent down to them and fed them’ (Ho 11:1-4). ‘For as a young man marries a virgin, so shall your sons marry you, and as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you’ (Is 62:5). ‘Therefore, behold, I will allure her, and bring her into the wilderness…I will betroth you to me in steadfastness, and in justice, and in steadfast love, and in mercy. I will betroth you to me in faithfulness; and you shall know the Lord…And there she shall answer as in the days of her youth, as at the time when she came out of the land of Egypt (Ho 2: 14, 19, 15). ‘Therefore, behold, I will allure her, and bring her into the wilderness’ (Ho 2:14). Indeed, some, like the prophet Jeremiah, are not be able to resist the allure of God: ‘O Lord thou has deceived me, and I was deceived; thou art stronger than I, and thou hast prevailed…If I say, “I will not mention him, or speak any more in his name,” there is in my heart as it were a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot’ (Jr 19: 7-9).

No less touching are the images with which God, before the advent of Jesus, presents Himself to His people as the ‘good shepherd’: ‘He will feed his flock like a shepherd, he will gather the lambs in his arms, he will carry them in his bosom, and gently lead those that are with young’ (Is 40:11). ‘I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep, and I will make them lie down, says the Lord God. I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I will bind up the crippled, and I will strengthen the weak, and the fat and the strong I will watch over; I will feed them in justice’ (Ez 34:16).

Mercy, therefore, sums up the whole of the Bible and expresses the very essence of God. It is no accident that the Book of Exodus, prior to every other definition, attributes to God the title of mercy: ‘The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin’ (Ex 34:6-7). This is the lapidary statement that the sacred text leaves us as an icon on which we should fix our gaze.

Father Rosario Messina

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram