With the approach of the event of the day of Camillian religious, Martyrs of Charity, as takes place every year our thoughts go to those who in recent centuries have sacrificed their lives to look after and care for sick people, and this includes the plague-stricken: ‘etiam pestis incesserit’.

More than ever before, this year the realities of events connected with the pandemic of the coronavirus catapult us into a situation that perhaps all of us believed had been relegated to the world of memories and no longer belonged to the present. Certainly, even if this plague has been faced up to with different instruments, the dedication and commitment of the new martyrs of the twenty-first century brings out in us once again even stronger emotions, as well as an awareness of our limits.

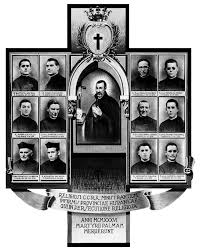

The obligation is evident to honour here a part of the considerable number of those witnesses to charity of the Ministers of the Sick who during the plagues of the seventeenth century lost their lives. Although they were aware, after expressly accepting the specific fourth vow of their Order, that in caring for the plague-stricken they would almost certainly have contracted the disease, they nonetheless gave themselves completely with generous devotion, love and competence, providing an example of charity that was out of the ordinary, and to such an extent as to deserve the appellation ‘martyrs of charity’.

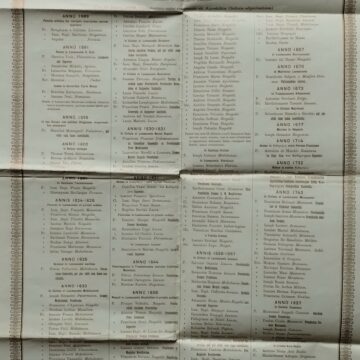

The first and certainly not the only victim of the plague that broke out in Palermo in 1624 because of a vessel that had not been put in quarantine and subject to disinfection was Fr. Giovanni Battista Pasquali.[1] He was remembered in the following way by Fr. Domenico de Martino, the Prefect of the Camillian religious house in Palermo: ‘A religious of much virtue and charity, he entered with so much fervour and spirit that he provoked amazement in those who saw him because he was untiring… After going to homes to administer the sacraments, and finding everyone sick, [after attending] to things of the soul, he turned to the needs of the body, that is to say making beds, lighting fires, giving food, and after [the sick] had eaten he washed the dishes, swept the homes, gave food to the children, and did everything those poor people needed’.[2] He died in Palermo on 31 July 1624 ‘of the plague, at the service of the plague-stricken’.[3]

The Order of the Ministers of the Sick was once again severely tested during the epidemic of 1630 that principally afflicted the cities of the North: Mantua, Milan, Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Borgonovo, Mondovì and Occimiano, where it had communities, and then spread to the Centre of Italy, to Modena, Lucca, Imola and Rome.

The Camillian religious involved in providing care to the plague-stricken, as well as the ‘purging’ and disinfection of correspondence, things and places, numbered about 120, of whom 56 died because they had become infected.

This time the pestilence had entered the Italian peninsula through the French and imperial troops who laid siege to Mantua in 1629. This city was the first to endure its very grave consequence. The inhabitants were reduced in number from 50,000 to 7,000. In his ‘Universal Chronicle of the City of Mantua’, the eighteenth-century historian Federico Amadei wrote: ‘there stood out above all the Fathers Ministers of the Sick who ran everywhere to give comfort to the dying poor’.[4] The prefect of the community, Fr. Giovanni Coquerel,[5] dedicated himself with generosity and devotion to caring for the sick and the dying in private houses and he himself met death on 6 April 1630. The same fate befell another nine Camillian religious, amongst whom is remembered Fr. Francesco Antonio Bucchiella.[6] The wards of the hospital were overcrowded and while awaiting the opening of a special plague hospital he had welcomed into the religious house as many sick people as possible. He died on 16 April 1630.

Milan paid a heavy price in terms of the number of victims: 15 professed (two fathers and thirteen brothers) and an aggregated member (Alessandro Amadei). Amongst the most well-known figures one may refer to the Milanese Camillian Br. Giulio Cesare Terzago[7] and Br. Olimpio Nofri. Br. Terzago had already announced the arrival of the plague in Milan in the autumn of 1629. Previously the head nurse in the hospitals of Naples and Genoa, he had there demonstrated his capacity and competence. During the plague in Palermo he fell gravely ill but managed to defeat the malady. He then moved to the large Ca’ Granda Hospital of Milan where once again he contracted the disease. However, once again he managed to survive it. He was then sent to the plague hospital of Santa Barnaba. Strengthened by his previous experiences, he performed his task with energy and great skill. This time, however, the disease did not spare him and he died shortly afterwards on an unknown date between August and September 1630.

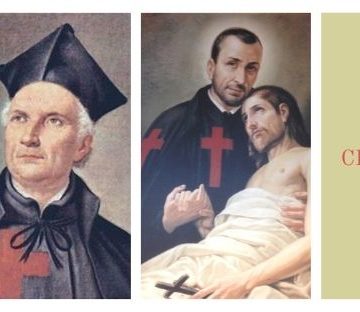

Another grave loss was Br. Olimpio Nofri[8] who came from Sienna. Ever since joining the Order in 1602 he had always dedicated himself with great skill and expertise, love and profound charity to service to the sick. The  Founder of the Order himself, in a letter addressed to the Superior of the community of Milan, Fr. Sorrentino, in which he sought to dissuade the latter from entrusting to Br. Nofri the task of attending to seeking alms rather than being the head nurse, wrote as follows: ‘leave Nofri in his post of ‘general nurse’ because he is one of those few men of whom one can say ‘he is worth a thousand men’ and he is ‘excellent’ in that post’. At the same time St. Camillus also wrote to Nofri telling him to stay in the hospital with his job ‘most willingly’, that he himself ‘very much wanted this’, and that ‘he would have achieved much’ if this decision was taken.

Founder of the Order himself, in a letter addressed to the Superior of the community of Milan, Fr. Sorrentino, in which he sought to dissuade the latter from entrusting to Br. Nofri the task of attending to seeking alms rather than being the head nurse, wrote as follows: ‘leave Nofri in his post of ‘general nurse’ because he is one of those few men of whom one can say ‘he is worth a thousand men’ and he is ‘excellent’ in that post’. At the same time St. Camillus also wrote to Nofri telling him to stay in the hospital with his job ‘most willingly’, that he himself ‘very much wanted this’, and that ‘he would have achieved much’ if this decision was taken.

Years later Br. Nofri, during the plague in Milan, took the place of Br. Terzago, who had gone to the plague hospital of Santa Barnaba, as head nurse at the Ca’ Granda Hospital. He worked very hard at his job without sparing his physical and spiritual energy and with that charity that had always marked him out. As soon as he had the first indications that he had been struck by the plague, he left the hospital so as not to be a danger to other people and moved to a house in the country that the Camillian fathers had received as a gift from Msgr. Besozzo. At the outset they had used this house as a dwelling when they were not in the hospital and now they made it into a refuge for religious who had been infected by the disease, calling it, for that reason, subsequently, the ‘house of death’. Here Br. Terzago awaited his death which arrived in August 1630.

However, it was in Bologna that the disease struck with so much violence as to cause an authentic massacre of the population. In the urban centre alone there were 13,398 victims out of 61, 559 inhabitants.

In this case, as well, in the struggle against the epidemic the Camillians were leading figures. They had been entrusted with caring for the plague-stricken in the plague hospitals and in private homes, as well as with the onerous and dangerous task of ‘purging’ letters and disinfecting places. [9] The prefect of the community, Fr. Giovanni Battista Campana,[10] was called to be a member of the Assunteria di Sanità, the urban health committee, which had the task of issuing directives to combat the spread of the epidemic. Unfortunately, however, as happens even today, there were voices outside the chorus that in contravening the rules did nothing else but create new and grave problems. In this case, the senate of the city authorised the so-called ‘pavillion’ fair to take place on 27 June. Accompanied by a solemn procession of penitence, this produced the devastating effect of a greater spread of the infection, overloading the plague hospitals, with the consequence that the plague-stricken were placed with those suspected of having the disease and those who were recovering from it. This led to an exponential increase in the number of victims of the plague.

The critical character of the situation required the sending to the city of new Camillian religious from Rome who were entrusted with enforcing the directives of the Assunteria Sanitaria. Each of the Camillians was given a neighbourhood of the city to watch over as general visitors. These were: Fr. Giovanni Battista Novati, Fr. Giovanni Paolo Zazio, and Fr. Ottavio Danieli, to whom was added, from Bologna, Fr. Francesco Prandi. A new organisational plan was drawn up for the health-care services which led to the opening of new plague hospitals in various parts of the city, this time divided between those who took in the infected, those for men, those for women, those for people recovering from the disease and those who were suspected of being infected. The task of these fathers, in addition to corporal and spiritual care for the sick, was to provide an update of statistics on deaths, infected people and people suspected of having the disease, with the data being written up in special registers so that the progress of the plague could be followed. A quarantine was imposed on those suspected of having the disease, at the end of which they could go out only after receiving prior written authorisation from the visitor of the neighbourhood.

The task of watching over the disinfection of homes or clothes that were infected or suspected of being infected by the plague was entrusted to Fr. Zazio. In coordinating the performance of this task, this religious had sixty men who were dressed in a white coat and carried a cane in their hand so as to be recognised. Father Zazio himself, who was very diligent and untiring in providing his service, fell ill but after recovering he dedicated himself to his job with even greater zeal, and to such an extent as to receive an award of merit from the prefect for health care and the senate of the city. A grave inflammation in his eyes, caused by dust from the zinc, lime, resin and other chemical substances that were used to disinfect the houses, provoked in him almost total blindness.

Both Fr. Campana and Fr. Zazio served the plague-stricken in other cities in Emilia Romagna. They both made a valuable contribution in Modena and Fr. Zazio also went to Ferrara and Imola.

Another four ‘Ministers of the Sick’, amongst whom Fr. Marapodio, died amongst the plague-stricken at Borgonuovo (Piacenza).[11]. Fr. Marapodio, after caring for the plague-stricken with compassion to the limit of his energies, was himself infected by the disease and he went to the feet of the Tabernacle to give his last breath in adoration. ‘This good father, made himself the Servant of everyone without distinction, in order to honour the Lord, because there were none who were afflicted or dying who did not receive help from his visits and his most pious hands’.[12]

At Mondovì another seven Camillian religious lost their lives. Amongst these were Fr. Pizzorno, Fr. Morelli and Fr. Lavagna.

In Florence and Lucca the massacre was felt less but nonetheless demanded from the Order another four glorious victims, amongst whom two were particularly known about: Fr. Donato Antonio Bisogni, in Florence, and Fr. Domenico De Martino, in Lucca.

A few years later, in 1656-1657, the plague reappeared, this time in Naples because it had been brought by the Spanish soldiers who had arrived from Sardinia. Once again it found the Ministers of the Sick ready to offer their lives to serve the sick. The disease felt no pity: ‘Death laid low ninety-six Religious who were priests’, of the hundred that had been alive before the plague. Many documents were lost and thus we only have the names of twenty-seven fathers, including Prospero Voltabio, Giovanni Battista Crescenzi, the Provincial Superior of Rome, Luigi Franco and Troiano Positani.

A few years later, in 1656-1657, the plague reappeared, this time in Naples because it had been brought by the Spanish soldiers who had arrived from Sardinia. Once again it found the Ministers of the Sick ready to offer their lives to serve the sick. The disease felt no pity: ‘Death laid low ninety-six Religious who were priests’, of the hundred that had been alive before the plague. Many documents were lost and thus we only have the names of twenty-seven fathers, including Prospero Voltabio, Giovanni Battista Crescenzi, the Provincial Superior of Rome, Luigi Franco and Troiano Positani.

Amongst the first victims was the Servant of God Br. Piero Suardi[13]. From an aristocratic Bergamo family, he had entered the Order in 1616 and since 1620 had worked at the Hospital of the Annunziata. Father Regi dedicated an entire chapter to him in his Memorie historiche…: ‘Our Brother Pietro Suardi, who saw such a great multitude of wretched people, since he burned with true and perfect charity, towards God and his neighbours; thus without any rest he intrepidly helped them so that with all due care those miserable sick people were served; where, with the closeness with which he treated them he came to contract the malady, as a result of which he had the good fate to be a forerunner for all the rest of our religious who were to imitate him in giving their lives for their neighbours’. [14] He died on 1 April 1656.

In Rome, in the meanwhile, in the same year Pope Alexander VII created a special ‘Congregation of Health Care’ and one of the decisions taken was the creation of a ‘purge of letters’ in a small villa outside Porta San Giovanni. This onerous and delicate task was entrusted to the Order of Camillians and involved all of the letters sent to the Holy See and to the representatives of the various States being subject to disinfection. A plague hospital was also established and equipped on the Tiber Island. Called to be the director of this institution after the death of the Capuchin Fr. Alessio Messana was the Camillian Br. Angelo Cicarante. With the spread of the pestilence another two disinfection centres were opened outside Porta Flaminia and thess were also entrusted to the hands of the Camillian religious. In one of these centres, known as the ‘unclean’ centre, authentic disinfection was engaged in of the clothes of people who had been admitted to the plague hospital (clothes of linen, hemp, wool and silk). In the other, known as the ‘clean’ centre, the final washing of these clothes took place. The plague caused the deaths of 15,000 people out of a population of 120,000 inhabitants. Amongst these there was also the death of the Superior General of the Order, Fr. Marcantonio Albiti, who died on Christmas day 1656.

In the spring of 1657 the plague reappeared again and was even more virulent, in the city of Genoa: in a few weeks reaped thousands of deaths. Because of the rapid increase in the number of infected people it became necessary at top speed to create new plague hospitals. Even the Pammatone Hospital, in which the Camillians worked, was converted into a plague hospital. The population had about 70,000 victims out of a total of 100,000 inhabitants. The number of victims amongst the Camillians was very high, and amongst them all we remember of the death of Br. Giacomo Giacoppetti.[15] Giacoppetti came from Ripatrasone, a small town in the Province of Ascoli Piceno. He entered the Order in 1612 after always wanting to imitate the work of St. Camillus and his religious, whom he had had an opportunity to observe at the Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Sassia when he was studying medicine and surgery. This wish grew in him and ignited in him his vocation, transforming him into a true Minister of the Sick. When the frightening pestilence that struck Genoa in 1656 broke out he went to the Pammatone Hospital where he worked without sparing himself in an attempt to alleviate the suffering of the plague-stricken poor. Very often he accompanied them to their deaths with devoted care and prayers, speaking to them about heavenly happiness, a generous compensation for all the evils of life on earth. Through his work he encouraged others to persevere even when faced with the natural fear of losing his own life. On 11 July 1656 the same martyrdom also awaited our Br. Giacomo who was struck violently by the disease which he had courageously challenged up to that moment. Transferred from his own cell in the ward of the infirmary next to his beloved patients, as he himself had predicted he died on 14 July, on the same day and at the same age as Father Camillus, of whom he was always a worthy son, true disciple and perfect imitator.[16]

same martyrdom also awaited our Br. Giacomo who was struck violently by the disease which he had courageously challenged up to that moment. Transferred from his own cell in the ward of the infirmary next to his beloved patients, as he himself had predicted he died on 14 July, on the same day and at the same age as Father Camillus, of whom he was always a worthy son, true disciple and perfect imitator.[16]

Naturally those offered here are only some exemplary models of a long list of Camillian religious who gave their lives with generosity through service to the plague-stricken. I am certain that many people know about the lives of these Camillian angels, but I am equally certain that none of us would have imagined that these touching pages of history of more than three centuries ago would have been so tragically relevant today, with the unleashing of this equally terrible enemy called coronavirus or covid-19. The current covid-19 hospitals are like the plague hospitals of yesterday. In the health-care rules provided by the Assunteria Sanitaria we can find some of the measures that today are suggested by the scientific technical committee of the government: the imposing of a quarantine on people suspected of having the infection and a prohibition on going out without authorisation; the disinfection of places and roads and the disinfection practised by the Camillian fathers; the request for personnel to help or to take the place of people who died doing their duty. We could also find very many other similarities but above all the identical dedication that the Ministers of the Sick have demonstrated in serving the sick in line with the precious teachings of Father Camillus himself: ‘If a man, inspired by the Lord God, wants to exercise the works of corporal and spiritual mercy, according to our Institute, he should know that he has to be dead to all the things of this world, that is to say relatives, friends, possessions, and to himself, and live only for the Crucified Jesus under the very soft yoke of perpetual poverty, chastity, obedience and service to the sick poor, even if plague-stricken, in their corporal and spiritual needs, day and night…which he will do for true love of God and to do penance for his sins, reminding himself of the Truth Jesus Christ’.[17]

In the hope that this emergency that we are living through will pass quickly, it only remains to us to pray and support with courage the admirable dedication and commitment of these new angels of the twenty-first century who, together with medical doctors, nurses and all health-care workers, are fighting and risking their own lives, and in some cases have tragically lost their own lives, for all of us.

[1] MOHR,41

[2] Sannazzaro Piero, Storia dell’Ordine Camilliano (1550-1699), Camilliane, Torino, 1986, 120

[3] AGMI 1520, f. 162 (17 ag. 1624). Negli atti di Consulta, diverrà la formula di rito per distinguere i morti nell’esercizio del ministero dagli altri morti occasionalmente di peste

[4] F. Amadei, Cronaca Universale della città di Mantova III, C.I.T.E.M.. Mantova 1956, 509-519

[5] MOHR, 215

[6] MOHR, 265

[7]Regi, 282-285; Mohr,233

[8] Mohr,238

[9]durante il loro servizio morirono il p. Pinocchi, il diacono Giuliano Guidetti e i fratelli Giovanni Battista Franchi e Andrea del Vecchio.

[10] Mohr,505

[11] Mohr,359

[12] Regi,286

[13] Mohr, 465

[14] Regi, p. 395

[15] Mohr, 439

[16] https://www.camilliani.org/fr-giacomo-giacopetti-un-grande-maestro-un-grande-discepolo/

[17] Bolla “Illius qui pro Gregis” di Gregorio XIV, 21 settembre 1591, art. 1

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram