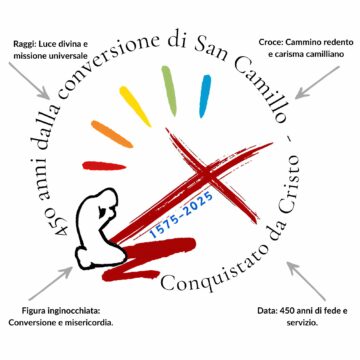

The celebration of the centenary of men of the character of Francis of Assisi and Camillus de Lellis cannot avoid the question of the contemporary relevance of their messages.

The celebration of the centenary of men of the character of Francis of Assisi and Camillus de Lellis cannot avoid the question of the contemporary relevance of their messages.

When reading the writings of St. Francis and the testimonies of his contemporaries which were collected in a volume that is almost three thousand pages in length and was published on the occasion of the eighth centenary of the birth of this saint, and following the events of the life of Camillus, one is led to invert the question: is there something that is not of contemporary relevance in the basic choices and the ideals of life of these two saints?

One could speak of a non-contemporary relevance of their work understood, however, in the sense of a forceful denunciation of the direction their epochs were taking. An individual interprets his epoch inasmuch as he expresses his own ways of seeing things but he also does this because he resists it and promotes dynamics that involve its rejection.

Francis belonged to a stage of economic and cultural rebirth of the medieval period. Camillus belonged to an epoch of rebirth when literary enthusiasms and confidence in men were effervescent. The former set forgoing things against the avidity of business and the seduction of money; the latter set people ignored and allowed to languish in hovels, in basements or attics, to whose aid he came, against men celebrated in salons with poems and academic discussions. It was right to praise the dignity of man but as long as he was in a state of despair it was not enough to exalt his greatness.

Francis and Camillus, notwithstanding the fact they were linked to their epochs and in thrall to them, set in motion a change of gear. On the one hand, they supported in an instinctive way the spirit of renewal of their epochs; on the other, supported by a evangelical vision of life, they pushed this to consequences which the intelligentsia of their times did not foresee.

The Terms of a Comparison

Between Camillus de Lellis and Francis of Assisi there were affinities of an external character that were purely fortuitous but also others of an internal character. The fact that both of them came from lives of gambling and war, were converts, experienced illnesses, and had to deal with the same problem of adapting what was ideal to historical-cultural situations and in part abandoning its integrity, were not elements that in themselves suggest that they had a closeness of spirit. Not even the radical way in which they offered their messages can be seen as something that was peculiar to them.

Their comparison becomes more stimulating as soon as one takes into consideration the features that mark out their spirituality: the crucifix, the sick, poverty, joy and universal brotherhood. Indeed, the explicit references of Camillus to Francis, whom he recognised as a model, are not sufficient to understand whether what motivated his soul was of a Franciscan impress. The nearness of these two men should be looked for above all in their spontaneous approaches which were devoid of intentional references to examples. Therefore, beyond a collection of biographical facts or episodes that are analogous in a literal sense, the comparison should be shifted onto the humus from which arose certain reactions in response to external interpellations.

It could be useful at the level of comparison to observe that Camillus was introduced to religious life in the friary of the Capuchins which had an unmistakable Franciscan spirit. And yet this particular, however valuable it may be, also remains an external fact that does not suggest that Camillus felt Franciscan. The role formative experiences shapes but does not create a person’s nature. The kind of sensibility that an individual has is decided by his nature. A legitimate affirmation of a Franciscan approach in Camillus can only come from an analysis of his ideals and his feelings rather than from the testimony of individual facts or sayings.

It could be useful at the level of comparison to observe that Camillus was introduced to religious life in the friary of the Capuchins which had an unmistakable Franciscan spirit. And yet this particular, however valuable it may be, also remains an external fact that does not suggest that Camillus felt Franciscan. The role formative experiences shapes but does not create a person’s nature. The kind of sensibility that an individual has is decided by his nature. A legitimate affirmation of a Franciscan approach in Camillus can only come from an analysis of his ideals and his feelings rather than from the testimony of individual facts or sayings.

A comparison, in addition to likenesses, offers differences of a psychological and cultural character. Around the figure of Camillus we encounter a scenario which was everything but idyllic like the landscape of Assisi where Francis worked. From Assisi, although it was afflicted by wars, he moved to Rome during the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth centuries. This was a Rome of fevers, flooding, famines, with plague and places of hopelessness ignored by official history but which Camillus revealed in all their nakedness. His determination was like that of a tenacious and obstinate wrestler whereas Francis had a more relaxed character and was ready to sing like a minstrel.

Camillus bound his life to the cause of sick people and he would never detach himself from them. After entering hospitals, only his death would lead him to leave them. His activities had only one horizon and they were moved by a single great passion – the person of the suffering.

And yet in him there was not a soul that offered the gospel according to the Franciscan spirit. The love of Camillus for the sick, the attention that he paid to the crucifix, his spirit of poverty and his very way of relating to nature belong to the river-bed of the Franciscan flow.

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram