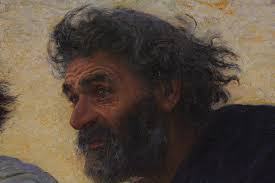

EUGENE BURNAND – Moudon (Switzerland) 1850-1921 ‘The Disciples Peter and John hurry to the tomb (Jn 20:1-9) 1898 – Paris, Musée d’Orsay

Two men dressed in an old fashioned way are running in the light towards a golden dawn while in the background hills and cultivated land stand out.They are running in a direction which is the opposite to the normal direction of the sun: from right to left. This makes us think of a return, of a second thought, of looking again at something that has already been encountered. They are going back to begin all over again, from the beginning.

Two men dressed in an old fashioned way are running in the light towards a golden dawn while in the background hills and cultivated land stand out.They are running in a direction which is the opposite to the normal direction of the sun: from right to left. This makes us think of a return, of a second thought, of looking again at something that has already been encountered. They are going back to begin all over again, from the beginning.

Where are they going? What are their ‘looking for’? What experience of a sign that is of an opposite character but of the same intensity could make them start afresh in the other direction?

John is the younger of the two; he has a clean-cut, young and beardless face; a penetrating look that is pushed forwards, searching for something, burning with a wish to find it. His seeing becomes increasingly intense until he believes. In the Greek – Jn 20: 1-10 – three verbs are used to indicate this ‘seeing’: one is ‘to realise’; another indicates ‘curiosity and looking for’ meaning in the object that is seen; and the third refers to ‘understanding with the insight of love’.

John is the only eye witness of the total humiliation of Jesus, the Son of God. Beneath the Cross, the majesty and the beauty, the fascination and the oratorical ability that he had learnt to love in Jesus are annihilated.

And yet John intuits that something does not add up, that it did not finish there. Standing at the foot of the cross with Mary, John discovers the nature of God and will write about in his letters: God is love.

His lips are semi-closed, his hands are clasped: his lips seem to hold back words. Differently from Peter, unable to contain his generous impulses, John expresses himself through the silence of faithfulness and the affectionate friendship typical of a teenager; he speaks little, he prefers to watch, to see and to hold back. In this he is similar to Mary who ‘kept everything in her heart’

Peter is slightly behind John. He is asking himself questions but his eyes do not look at a precise point: in him there is an emptiness that has to be filled. He had an impassioned attachment to Jesus that was impetuous and intense. Thus it was also painful but tended to express itself in a possessive and violent way. Now he is experiencing within himself the drama of the humiliation of his denial, the bitterness of sin and the meaning of his own baseness. His face reveals dismay, anxiety, incredulity and unexpected surprise.

Behind Peter, just indicated and only to be seen with difficulty, the painter has put three beams in memory of the cross of Good Friday. They are behind him because this is the morning of a new day.

Behind Peter, just indicated and only to be seen with difficulty, the painter has put three beams in memory of the cross of Good Friday. They are behind him because this is the morning of a new day.

The paschal annunciation of the victory of Jesus over death is entrusted to these hands – to Peter’s hands: strong and rough hands, the hands of a man who faces up to the hard reality of life without fleeing and without illusions, and yet hands that are robust, hands which when they encounter those of other people transmit faith, hands that build up the Christian community of the Risen Christ.

The Austrian philosopher Wittgenstein in 1937 wrote: ‘Christianity is not a doctrine, it is not a theory about what has been and what will be a human soul but, rather, it is a description of a real event in the life of man’. This is precisely the reason for the joyous amazement impressed on the faces of the two disciples who are running to the tomb of Easter.

Grant that it may also be in this way for all of us:

May our faces be lit up

By our marvellous observation

Of the morning of Easter.

Yes, we are certain about it: Christ truly rose again.

You, victorious King, have pity on us!

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram