Fifty years after the promulgation of the encyclical letter POPULORUM PROGRESSIO of Pope Paul VI (26 March 1967)

This is the fiftieth anniversary of the great social encyclical of Paul VI, Populorum progressio (26 March 1967). The central axis of the entire encyclical is development and here we find a very fine definition made by Paul VI: ‘Development is the new name of peace’.

This is the fiftieth anniversary of the great social encyclical of Paul VI, Populorum progressio (26 March 1967). The central axis of the entire encyclical is development and here we find a very fine definition made by Paul VI: ‘Development is the new name of peace’.

As Paul VI states in Populorum progressio, one of the fundamental tasks of the actors of the world economy is to achieve integral and solidarity-inspired development for humanity, that is to say, ‘the promotion of each man and of the whole man’. This task requires a conception of the economy that assures at a world level a fair distribution of resources and corresponds to an awareness of the economic, political and cultural interdependence that unites the peoples of the world in a definitive way and makes them feel that they are connected to a single destiny.

This encyclical of Paul VI lays a great deal of emphasis on the fight against poverty. The principle of solidarity, in the fight against poverty as well, must always be flanked by the principle of subsidiarity, thanks to which it is possible to stimulate a spirit of initiative – which is the fundamental basis of all socio-economic development – in poor countries themselves. One should not look at the poor as a problem but as those who have to become the subjects and protagonists of a new and more human future for the whole of the world.

In the social thought of Paul VI, the safeguarding of the creation plays a crucial role because if man destroys the environment he ends up by destroying himself. This thought was taken up with great vigour by Pope Francis in his social encyclical Laudato sì on care for the common home which was addressed to all men on earth. Christians, today, are called upon to place themselves at the ‘service of the integration of the poor into society and at the service of reconciliation in the world’. This is because ‘the message of the Gospel today passes by way of the healing of bodies and service to the frailest beings in order to flow into the communion of peoples’.

And where fifty years ago Paul VI pointed out to humanity a ‘progress of peoples’, this development today must develop, according to what Pope Francis invokes, into a ‘communion of peoples’ and the key by which to achieve this is Mercy. ‘As the word itself says, this is a matter of caring for those who live in misery. This is a new sensitivity that enables us to be touched by the other and leads us to develop a new way of acting’.

‘The progressive development of peoples is an object of deep interest and concern to the Church. This is particularly true in the case of those peoples who are trying to escape the ravages of hunger, poverty, endemic disease and ignorance; of those who are seeking a larger share in the benefits of civilisation and a more active improvement of their human qualities; of those who are consciously striving for fuller growth’.

The first paragraph of the encyclical immediately goes to the centre of its subject. It does this with a historical perspective that had been hitherto unknown because it examines the world as a whole. For the first time, the subjects, the problems and the prospects of the entire planet are perceived with the employment of an overall outlook.

On 26 March 1967, Paul VI addressed Populorum Progressio – an encyclical dedicated to the subject of the development of peoples – to ‘all men of good will’ The ecumenical Second Vatican Council had just come to an end: it had opened up universal perspectives which were ‘ecumenical’ and amongst these was hope for liberation from backwardness and injustice as the fundamental basis for the recognition of the rights of the poor and the last. Shortly before the publication of this encyclical, Paul VI had established a special pontifical commission, called Iustitia et pax, based on a phrase of the Prophet Isaiah according to whom ‘peace is the ‘work’ of justice’ (Is 32:17).

A sign of the times

By his Populorum Progressio, Paul VI addressed all men and not just Christians. For some people this encyclical dealt with a subject that went beyond the normal ‘religious’ concerns of the Church. Hitherto the economic and social field had been entrusted by traditional morality to the responsibility of the State; however, it remained detached from considerations of an ethical and moral kind.

This encyclical, therefore, marked a new step forward on the journey of the social doctrine of the Church. It was a logical deduction from the doctrine of the Second Vatican Council as expressed in Gaudium et Spes and from the previous social doctrine of the Church whose horizons it expanded going from the condition of workers, which had been examined in Rerum Novarum, to the development of the peoples of the entire planet.

The aspiration to the development of all peoples appeared immediately and was seen as a ‘sign of the times’. For the first time in history these issues and problems were approached from a planetary perspective with a new look at the dynamics of the relations between States, populations and ‘worlds’.

Living solidarity

In his Populorum Progressio, Paul VI pointed to development as the great theme of the Church (four years later, at the Synod of 1971, the bishops said that preaching justice was the constitutive element of the mission of the Church) but also of the whole of humanity on its journey towards peace. Peace was a real concern in that historical period as well, a period that was characterised by the ‘Cold War’ between the superpowers, by the conflict in Vietnam, and by the explosion of conflicts in the Middle East. The great innovation of this encyclical was provided by what it said about the new breadth acquired by the social question, which no longer related to a single category – the workers – or to a part of the world – the West. Instead, it related to the whole world because of that interconnection between developed peoples and developing peoples that was by now becoming a daily experience because of the development of social communications. From this new relationship derived the ethical commitment to live solidarity and thus ‘It is a very important duty of the advanced nations to help the developing ones’.

For Paul VI, just any kind of development, limited to the economic field, was not sufficient. He pointed to an authentically human and integral development because the development of nations could not be separated from the needs of solidarity.

Development as a pre-condition for peace

A further historical innovation of Populorum Progressio was the connection that the Pope established between development and the peace of the world. This was expressed in a principle that was to enter history: ‘Development is the new name of peace’. Indeed, the need for social justice could no longer be met except at an international level. To neglect it, could unleash the violence of the poor: what was called ‘the fury of peoples’. It was not possible to think of the development of a people if that people continued to be denied access to world trade or if only weapons were offered to it for war.

The root of this innovation was a vision of human beings and society that Paul VI drew from the Christian anthropological outlook and from the personalist philosophy of his time: man is a being who transcends himself and his dimensions because he is marked by likeness to God, the creator of his freedom and dignity; a God who is in a relationship with, and is open to, everyone.

Towards a new and solidarity-inspired world

Populorum Progressio, which was greeted as a sign of hope above all in Africa and Latin America bore within it the force of a utopia: that of believing in a new world in which, finally, the poor of the earth would have their dignity restored to them, as well as the possibility of acceding to those essential goods which over many centuries had been taken from them by the greed of the rich peoples of the world. The sense of this trust in the future and in the possibility of redeeming the marginalised is also to be seen in the choice – and this was not a matter of chance – of the date of publication: Easter Sunday (26 March 1967). The Church chose the pathway of a historic commitment; she placed herself on the side of the last; and she herself decided to be poor with the poor, trusting only in the force of the Gospel rather than in the wealth of means. In this way, evangelisation and human promotion became inseparable.

Populorum Progressio pointed to the road of an industrious faith that is not frightened by the dust of history and that knows how to take on the concrete problems of the world. Thanks to the Church, the peoples of hunger and under-development – who had been reduced to this state by the unfair distribution of wealth – irrupted on the scene of the Western world which stubbornly continued to be blind and deaf to the imbalances of the planet and wanted to defend for itself the wealth that had been accumulated, the result – amongst other things – of the exploitation of the poor and a world economy without rules except those of the market and profit.

A profound contemporary relevance

Over fifty years since its publication, Populorum Progressio still displays its profound contemporary relevance. The globalisation of markets; an economy that is often without rules; a lack of world governance of fair and solidarity-inspired development; profit seen as the new god to which it is even licit to sacrifice human lives; and the idea that keeping the peace is not linked to the full development of peoples but to the use to weapons, all indicate how the conditions of inequality have become worse and the gap between rich countries and poor countries has grown. Furthermore, notwithstanding the praiseworthy commitment of many Christian communities, of civil society and of very many non-governmental organisations, governments and international organisations do not manage to make decisive choices to ensure that the scandals of hunger, of poverty, of early deaths, and of a lack of recognition of essential human rights find short- and long-term practical pathways that achieve a solution. It is evident that we have to change direction and to choose the demanding pathway of a new model of development, of cooperation, of welcome, and of dialogue between cultures.

The validity of what it proposes

What Populorum Progressio proposes, and this is as valid as ever, can be summarised in three ‘duties’.

Solidarity is perhaps the one that is the easiest and the most practicable. To overcome hunger, illiteracy and ignorance campaigns are no t enough. They are, indeed, promoted, but often they are limited to dealing with an emergency. Paul VI observed that medium- and long-term programmes are needed to build ‘a human community in which men can live truly human lives, free from discrimination on account of race, religion or nationality’. But for this to occur, a solidarity must be developed which impedes the accumulation of the superfluous and instead makes it available to the weakest peoples of the earth.

t enough. They are, indeed, promoted, but often they are limited to dealing with an emergency. Paul VI observed that medium- and long-term programmes are needed to build ‘a human community in which men can live truly human lives, free from discrimination on account of race, religion or nationality’. But for this to occur, a solidarity must be developed which impedes the accumulation of the superfluous and instead makes it available to the weakest peoples of the earth.

The second duty relates to a ‘social justice’ where all the peoples of the world can take part in international trade. The meetings of organisations such as the World Trade Organisation and the G8, which brings together industrialised countries, show how difficult it is to find an agreement that allows the poorest countries to enter world trade without being disadvantaged. Above all if – as indeed often happens – poor countries are invited to take part in world trade with their products, above all agricultural ones, which they do not manage to sell because of the competition of rich countries which are helped by their governments through protectionist measures or subsidies for producers that act to impose their products at competitive prices…Paul VI was a prophet indeed when he stated in Populorum Progressio that ‘it is evident that the principle of free trade, by itself, is no longer adequate for regulating international agreements’.

The third duty to which Pope VI appealed is as of much contemporary relevance as it has ever been during this epoch of globalisation, exclusion, international terrorism and war. Paul VI observed that ‘the world is sick’ not because the resources are not there but because of a ‘lack of fraternity between men and peoples’. At the same time, he made certain recommendations that are also valid today: mutual hospitality and fraternal welcome and a social sense with which industrialists, experts and volunteers should make themselves available to the weakest countries of the world in order to offer them their contribution in a disinterested way. This is what in Populorum Progressio is pointed to as the duty of universal charity. In reality, only this will manage to create a new world marked by the peace and ‘dialogue between civilisations’ that Paul VI evoked: ‘Sincere dialogue between cultures, as between individuals, paves the way for ties of brotherhood. Plans proposed for man’s betterment will unite all nations’

Read the whole text of the encyclical here:

http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/it/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_26031967_populorum.html

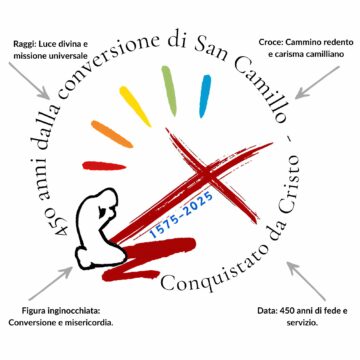

Camillians on Facebook

Camillians on Twitter

Camillians on Instagram